Most of the day, passengers boarding a Green Line trolley from a street-level stop board through the front door and use the farebox to validate their passes and pay their fares. During rush periods, operators also open the rear doors for passengers with passes to board more quickly. Recently, the MBTA conducted a study of how much fare revenue might be lost by allowing boardings through the rear doors. This post describes how we designed and conducted the Green Line Rear Door Revenue Loss Study.

Observing Boardings on 110 Ride-Along Trips

The main challenge in this study was distinguishing if someone boarding at the rear doors:

- had a valid pass or paid on the platform;

- walked to the front of the car to pay at the farebox; or,

- didn't pay their fare.

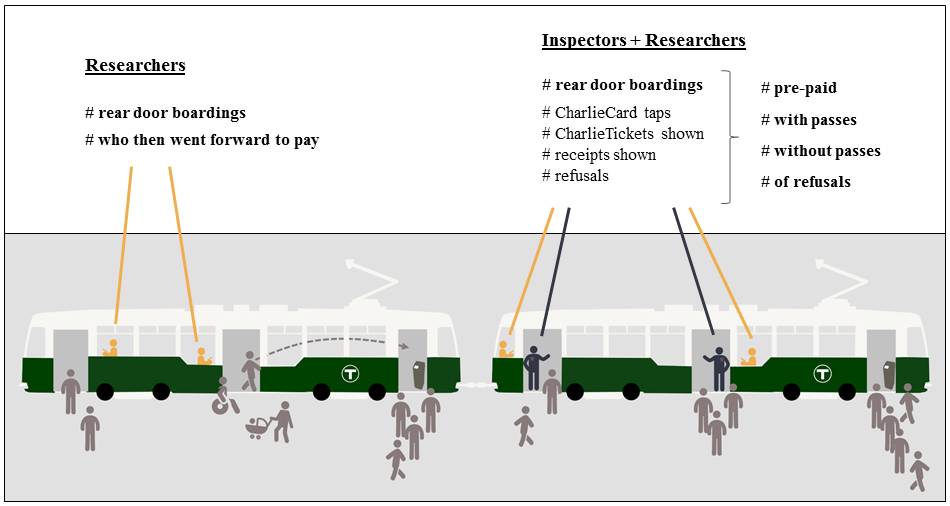

From previous studies, we had estimates of how many people entered the rear doors. But we knew that some of those people either had passes or already paid on the platform. We needed to ask passengers to show their card or ticket and also see whether they would go to the front farebox to pay. At the same time, we wanted to disrupt the boarding process as little as possible. We located our teams as far inside the vehicles as possible to reduce behavior change.

We focused our sampling on time periods with the highest surface boardings for each branch. These are periods when rear doors open the most, and when existing data indicated that trains had the most rear door boardings. While the B, C, and D branches show a typical AM boarding peak in the inbound direction, the main travel peaks on the E branch are inbound from the Longwood Medical Area surrounding the PM peak period. We sampled a few other trips throughout the day from 6:30 AM to 6:30 PM because we also knew that operators open doors on some particularly crowded trips even in periods that are not generally crowded.

To ensure that passengers understood that the request to see their card or ticket was legitimate, each researcher traveled with a Green Line official who asked the passengers for their fare media, while the researcher wrote down counts in a number of categories. Each official asked passengers to tap their CharlieCards to a prototype inspection device, which did not deduct fare but rather stored card information in order to look up whether each card had a pass or not. See our animation of how passengers tapped CharlieCards to the prototype device:

By asking passengers to show their card or ticket, and by traveling with a Green Line official who was typically in uniform, we might have influenced where some passengers boarded. We believe that by staying well inside the vehicle, most passengers did not notice us until they were already most of the way to the front of the line trying to board. Additionally, this configuration meant that most passengers who moved to another door once they saw an inspector would have done so suddenly. Researchers counted that behavior as intentional fare evasion. We did not see many passengers trying to avoid officials; in fact, we saw more passengers bumping into officials because they didn't see them at all.

In normal operations, some passengers first board at a rear door and then go forward to the farebox to pay. This process is disrupted when an official asks to see a pass or fare. For each trip that we observed, we placed the officials and inspectors to intercept passengers on one car, and placed researchers only on the two doors of another car to inconspicuously count rear door boardings and the number of passengers going forward to pay. See our animation of how researchers saw an occasional passenger going forward to pay:

Thus, for each one-way trip, the research produced a total count of rear door boardings, a breakdown of how many passengers had passes, and a breakdown of how many went forward to pay. As shown in the diagram at the top of this post, these variables needed to be tabulated and integrated in order to estimate fare loss.

Integrating Data Across 3,194 Rear Door Boardings

The expected revenue loss per trip depends on both the number of passengers boarding without a pass and the number of people who went forward to pay. Since we couldn't collect these two variables from the same train car, we had to use as much data as possible from each car on a particular trip to form an estimate of how much revenue was lost on both cars of that trip. Additionally, some information had to be aggregated across similar trips, categorized into 12 groupings. Each grouping contained either Inbound or Outbound trips matching one of the following:

- AM Peak trips on B, C, and D branches;

- AM Peak trips on the E branch;

- Off-Peak trips on B, C, and D branches;

- Off-Peak trips on the E branch;

- Extended PM Peak trips on B, C and D branches; or

- Extended PM Peak trips on the E branch.

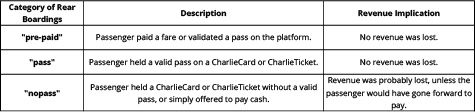

To analyze the data from rear doors where officials asked for passes, we tabulated boardings at those doors into four categories. Counts that the researchers observed directly could simply be added up. For CharlieCards that tapped the inspection device, we looked up how many had appropriate passes active at the time they were tapped. When a few cards on a trip did not register a tap with the prototype device, we inferred their pass status from other cards on the same trip. We now had enough data to create four totals for each trip, as shown in the table below.

To analyze the data from rear doors where researchers simply observed boardings, we tabulated all rear door boardings at those doors and then calculated a “farebox approach ratio.” The farebox approach ratio is the proportion of rear door boardings who then went forward to interact with the farebox. We calculated this ratio first by trip, and then by grouping.

Since we did not observe how many of the passengers who went forward to pay had passes, we had to make assumptions about who goes forward to interact with the farebox. To create an estimate of revenue loss, we used a range of assumptions about the pass rate of the passengers going forward to pay. Out of the passengers who go forward to pay, if more of them had passes, the revenue loss would be higher. The result is a Low and High estimate of revenue loss per trip based on the assumed pass rate of those going forward to pay.

Results

The annual estimate of revenue loss from rear door boardings on the surface green line is $1.6 to $1.9m. In comparison, the MBTA collects $95.0 million in annual Green Line revenues. For each grouping above, we calculated the actual number of Green Line trips run per year in that time of day, branch or branches, and direction. Then we multiplied that number by the average revenue loss observed per grouping.

Losses were highest on those trips that were most crowded. High levels of crowding not only increased losses per trip, but also per passenger. In order to estimate crowding, we calculated total surface boardings (rear door + farebox). The most crowded inbound trips had a higher proportion of rear door boardings than other trips. As a result, reducing spikes in crowding would spread the load over more trains that were less crowded, and reduce total revenue losses.

Conclusion

The current combination of MBTA boarding policies and service delivery on the Green Line focuses on speeding boarding times and improving service quality, but also leading to an estimated $1.6 to $1.9m loss of fare revenue.

Our research into revenue losses from rear door Green Line boardings has multiple applications for improving MBTA service and efficiency. In order to both reduce revenue losses and speed boarding times, the MBTA is evaluating options for changing the times and stops at which officials currently collect fares from passengers on the platform. These changes would optimize the total fares collected, staff time, and reliability of service. Additionally, this research shows that improvements to Green Line reliability will also improve fare collection.